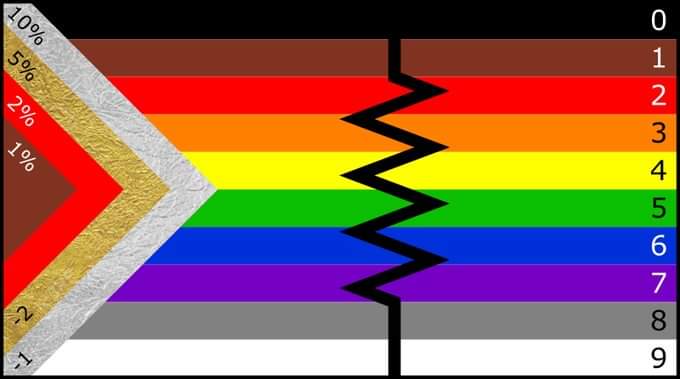

Resistor colour codes. There are 3 and 4 band types of resistors, so have a google around and learn how to read them. Here is a colour chart for starters.

Construction basics

Constructing a radio project can be a daunting experience at first, but with a few new-found techniques and some practice it becomes a new skills for life. All competence comes from shaky beginnings, and allowing one’s self to make mistakes and learn from them. Added to this, there is no substitute from some good old learning from the ground up.

Here are a couple of mottos well worth adopting: a) Learn it right, do it well. b) Do it once, do it right.

As for me I started playing with valve radios in about 1960 at the age of 8. There was no one to learn from so many mistakes were made, along with a few hair-raising tingles and shocks! At 17 I started an apprenticeship with Marconi-Elliott Avionics. One of the best apprenticeships around, and in these pages my plan is to pass onto you some basic but high quality lessons, so you can learn to solder, wire and construct this and other projects with confidence. OK, here we go:

Suggestion

If you are not yet good at the art of soldering and construction, to build this project you will need to upskill. To do this learn as much as you can from anywhere. YouTube, friends and especially the constructors at your local radio club. I would suggest you get a bunch of scrap boards and learn to carefully de-solder and remove components, then it won’t matter if any are destroyed. Don’t give up hope, you can learn this, you really can. In the past I have felt like giving up on a few occasions with something particularly difficult, and this motto / mind-coach has kept me going to the point of being tenacious! “If anyone else can do this, so can I”, “This is just a learnt skill, and yes I can learn it too”. So keep your chin up and move forward and never give up!

Basics

- Soldering. Always make a solder joint quickly, and do not leave the heat on a moment longer than necessary. This is called keeping the joint ‘wet’, when there is still some flux on it. The reason for this is that as soon as the solder stops smoking, the flux is all burned off, and the solder will turn to something resembling chewing gum! If a joint is like this, or the solder is drawing away on the iron bit – then try carefully and quickly adding a tiny bit more solder (and with it flux) and the joint should take form again. If there is just too much solder around, then use a solder-pump or solder-wick and remove the solder. Again, quick as possible so as to not over heat wire or tracks and do damage. Use the right heat for the type of solder too.

- Tinning. Unless a component is new and shiny, all wires, terminals and anything being soldered must be cleaned and tinned first, that is each individual part. If the solder won’t take to the part, then it will never make a good joint, do don’t proceed until the part is cleaned and tinned (scratched with tweezers, wire wool, emery etc). Only two well tinned parts will make good joint.

- Wire preparation. With any multi stranded PVC wire follow this importance process. Strip – Twist – Tin. Strip off the insulation baring the wires carefully so as not to damage the wire. In amateur work (but never professional such as avionics) you can get away with doing it with cutting pliers, using the reverse edge. If it is PTFE wire crush the wire with pliers at the end and then pull back the two outer insulations with pliers. Next Twist the strands well together. Last Tin the wire. Hole the soldering iron but under the wire near the but (The but is where the insulations stops), and ass the solder to the other side of the wire, and when the solder flows around and through the strands move both bit and solder down the wire to the end where is was cut off. The reason to start at the but is that the heat is moving away from the insulation and it will not get burned and melt. (In the apprenticeship we all had to cut off 250 pieces of 7/.02 PVC wire, that is 7 strands of .02″, and do ‘wire preparation’ on both ends, so 500 prepared wire ends. They were all then inspected with a 10x magnifying glass, and any less than perfect rejected. Practice makes perfect right?.

- Mechanical joint first. If this is not a PCB through hole or Surface mount part, a mechanical connection is made first. Wrap say a wire around a pin or tab and make it fast with snipe nosed pliers. If the pin, or tab has a hole in it – Don’t use the hole! It is a darn pain to get off if needed in the future! Just wrap and secure the wire to the whole outside of the tab. On a pin wrap it 270º with the PVC outer very close to the pin. On a terminal it is 180º. (See drawing)

- Soldering the joint. First, wipe the bit on your damp sponge cleaner. The bit should now look bright and shiny. If not then use a solid flux dip, and re-wipe it on the sponge. You might have to put a tiny bit of solder on the iron bit first, and then put the iron onto the joint to be soldered. Again, after a second or so add the solder ‘to the OTHER side of the joint’, and not to the iron bit. The reason for this is that solder always tries to seek the heat, and you will see the solder flow around and through the joint towards the bit. Keep adding the solder until it is well flowed, and there is enough to make a slightly concave finish. Too little and you won’t see the solder enough, too much is convex, or bulging out. This operation should take 2 to 3 seconds. On a PCB 2 seconds is plenty for a through hole component, and for an SMD part 1 second. I was taught ‘the three second rule’. More than 3 seconds and the joint is likely to be a dry one (remember, that lack of flux above).

- Surface Mount parts. If you dislike fiddly SMD parts, first make friends with the job so you enjoy it and do it carefully. Don’t rush, it can be enjoyable if you tell yourself it is – and it then is. Get it? In the HamPi the smallest SMD parts are 0805, others are larger, and easier. I find it best to pop a tiny blob of solder on ONE of the pads for the part on the PCB. Next fold the component with small tweezers (use stainless steel ones) and solder the one leg in place making sure the part is in the correct orientation and straight. Next solder the other legs in place. Now check VERY CAREFULLY with a 4x or 5x magnifying glass. This is so worth it. the inspection in groups or as a whole board. Have all the legs soldered well? I still got a couple of poor joints on the last CPU board, after all these decades!!! (Remember the motto; Do it once, do it right. It is a lot quicker to do a job and inspect it to find issues and fix them later, as it is also true it is easier to put in a fault, or wrong component than to fix it!).

- Order. Fit the small parts first. Resistors, Capacitors, Diodes etc. This is because larger parts get in the way and it is too easy to burn them getting to smaller parts with the soldering iron – and that makes a job look bad. Next the transistors, then the through hole parts and large parts. I usually do the electrolytic capacitors last, as the PVC covering is easy yo burn, is smelly, and just looks bad.

- Coils and transformers / ferrites. This is fiddly, and made into fun too. There are a fair few coils to wind in this project, especially on the Radio board. The design has not shied away from them, because coils, toroids and small transformers are a quality way to avoid distortion, and they transform impedances well. Many commercial rigs avoid them because of the manufacturing expense, but this is a hobby and we are after quality at every point, not cost cutting mass-production. Cut the correct length of enamelled copper wire and using a scalpel or such blade hold the wire and scrape off the enamel from one end for about 5mm. Now carefully wind the part making sure to not damage the enamel while winding. Some ferrites have sharp edges and it is easy to damage the enamel coating. While bare copper in contact with the ferrite won’t matter, as ferrite is an insulator, the worst thing that can happen is to get shorted terns – and this will be very hard to fault find! In general try not to overlap the wire, but getting the turns side by side. This is not that crucial, it is good practice and looks nice! If there are a lot of turns and a complete 360º is covered, just carry on. It is ok. A couple of other things. One turn is counted as the wire passing through the hole once in a ring-core. For a binocular core (2 hole), one turn is the wire passed through one hole, and then back through the other hole to where the turn was started. This means that if you count the turns on the outside of a ring core it will count as one LESS. The wire will pass through say 10 times, but one outside you count 9. Some transformers are Bifilar would. Google this, it’s easier. In this project each coil / transformer will have it’s own building details. Another tip. In general the thickness of wire is not precise. If you have similar sized wire it will most likely make zero difference as long as it fits. Exceptions to this will be mentioned. (So if you need 0.2mm and only have 0.23mm wire, use it).

- Much more to come!

![]()